Unnao History : For many in the modern era, the name is recognized due to recent political and social events. However, for the historian and the traveler, Unnao represents a continuous thread of human civilization stretching back over 1,500 years.

Located in the heart of Uttar Pradesh’s Awadh region, Unnao is not merely an administrative district carved out by the British; it is the custodian of “Lauta Shahr” (The Returned City) , the land of the legendary Raja Sujan Singh, and a vital piece of the Kosala janapada. To truly understand the Awadh region, one must understand the layered history of Unnao.

In this extensive guide, we will navigate through the ancient tells (mounds), the medieval mysticism of Sufi saints, the administrative genius of Akbar, and the colonial restructuring that gave us the modern district map.

1. The Ancient Canvas: Unnao in the Epic and Buddhist Eras

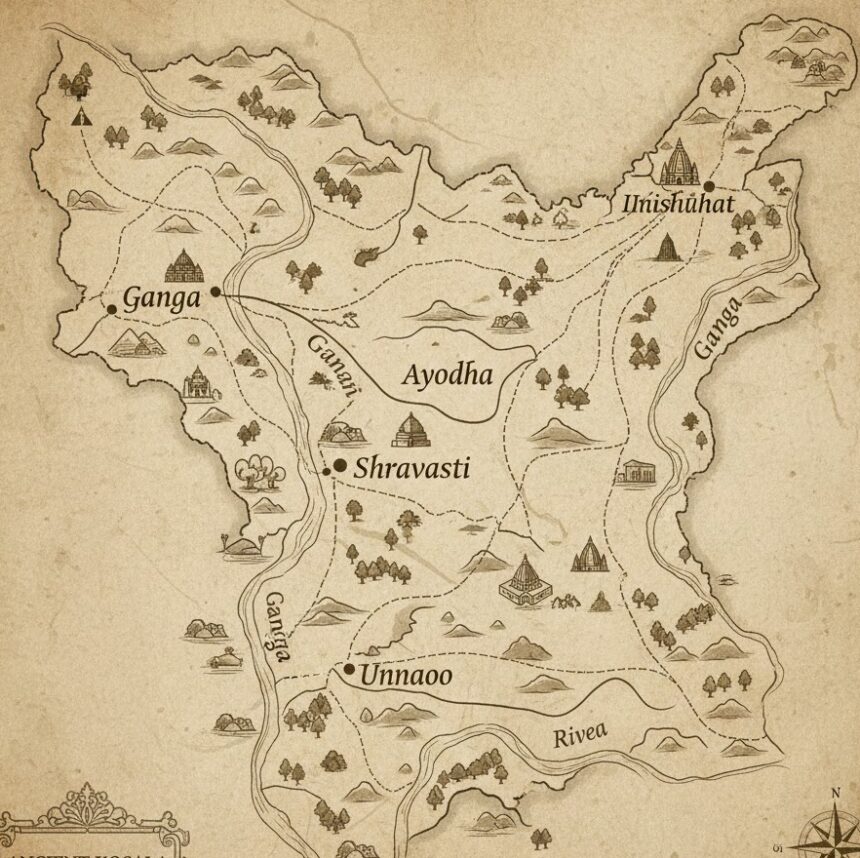

Long before it was a district, Unnao was geography. The land between the Ganga and Sai rivers placed it firmly within the ancient Kosala Kingdom. In the time of Lord Rama, this region flourished under the rule of Ikshvaku dynasty kings.

Archaeological surveys conducted in the 19th and 20th centuries revealed Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW) in various mounds across Unnao. This pottery style is indicative of the Mauryan Empire (322–185 BCE) . It suggests that while the urban elite were managing empires from Pataliputra, the fertile plains of Unnao were teeming with agrarian settlements and trade outposts.

The official government records note that remains found in the district testify to “very early times.” Specifically, the presence of Buddhist monasteries (Sangharamas) recorded later by Chinese travelers confirms that this area was not a rural backwater but a significant node in the Buddhist circuit that connected Kannauj to Sarnath.

2. The Landmarks of Antiquity: Hiuen Tsang’s “Navadevakula”

The most concrete evidence of Unnao’s ancient glory comes from the travels of Hiuen Tsang (Xuanzang) . In 636 AD, during the reign of Emperor Harshavardhana, this Chinese pilgrim spent three months in Kannauj, the imperial capital.

According to his memoirs, Tsang traveled approximately 26 kilometers northeast of Kannauj. He arrived at a city called Na-fo-ti-po-ku-lo, identified by scholars as Navadevakula (New Abode of the Gods). This city stood on the eastern bank of the Ganga.

Where is this today?

Historians have placed this location approximately 3 kilometers northwest of Bangarmau in the Tehsil Safipur of Unnao. Tsang described a city 5 km in circumference. He documented:

-

A magnificent Deva Temple (possibly Hindu, given the name).

-

Several Buddhist Monasteries.

-

Numerous Stupas.

This description indicates a rare moment of religious syncretism in 7th-century India, where Hindu temples and Buddhist Viharas coexisted in the same urban center.

3. The Legend of Aundha Khera: The City Overturned by a Curse

While official records are clinical in their description, the local folklore of Unnao breathes life into the ruins. The site identified as Navadevakula is locally known by two haunting names: Aundha Khera (The Upturned Fort) and Lauta Shahr (The Returned City).

The Curse of the Sufi Saint

Legend states that this prosperous city, with its high walls and bustling markets, was home to a king who lacked humility. A Muslim saint (Sufi) arrived at the city gates seeking shelter or alms. He was turned away or mistreated by the arrogant ruler.

Enraged by the lack of compassion, the saint cursed the city. In a single night, the city was “upturned” . Palaces sank into the earth, and the streets inverted. When morning came, the city was gone, replaced by flat land.

Today, the Dargah (tomb) of that saint stands at Bangarmau. The government records specifically note this is “perhaps, the oldest Muslim monument in the entire district.” This fusion of Buddhist archaeological sites with Islamic Sufi lore creates a uniquely Unnao tapestry of history.

4. Medieval Unnao: Parganas, Chaklas, and the Mughal Administration

To understand how Unnao became a district, we must understand the Mughal revenue system. During the reign of Emperor Akbar (1556-1605), the region was integrated into the Sirkar of Lucknow, which was part of the Subah of Awadh.

The Mahal System

Akbar’s administration divided land into revenue circles called Mahals. The official district history notes that these Mahals were the direct predecessors of the Parganas we see today.

This system created the administrative skeleton of Unnao. Villages were grouped into Mahals, which later evolved into the Pargana names we still use: Bangarmau, Safipur, Mohan, and Purwa.

5. The Nawabi Era: The Baiswara and Purwa Chakla

As the Mughal Empire weakened, the Nawabs of Avadh gained autonomy. The revenue map of Unnao was redrawn. The region was divided into administrative units known as Chaklas.

The Eastern and Northern Divisions

-

Chakla Purwa: The eastern portion of modern Unnao formed the core of this Chakla.

-

Chakla Rasulabad & Safipur: These covered the northern regions.

-

Baiswara Tract: This is historically significant. Parganas such as Patan, Panhan, Bihar, Bhagwantnagar, Magaryar, Ghatampur, and Daundia Khera were part of the Chakla of Baiswara.

Note: At this time, Baiswara was primarily administered from Rae Bareli. This explains why, in 1869, these Parganas were “transferred” to Unnao—they were geographically closer to Unnao’s Purwa Tehsil than to Rae Bareli’s capital.

6. The 1857 Uprising and the Birth of the District

The year 1856 was a watershed moment for Awadh. The British East India Company, under Lord Dalhousie’s ‘Doctrine of Lapse,’ annexed Awadh, imprisoning Nawab Wajid Ali Shah. The region erupted in rebellion just a year later.

Purwa becomes Unnao

Initially, the British established a district called “Purwa” . Its headquarters were stationed at Purwa town. However, the administration quickly realized that Purwa was not geographically central.

The Shift:

In a move that would define the modern identity of the region, the British shifted the district headquarters from Purwa to the town of Unnao. Thus, the district was renamed.

At its inception in 1856, the district contained 13 Parganas:

-

Bangarmau

-

Fatehpur Chaurasi

-

Safipur

-

Pariar

-

Sikandarpur

-

Unnao

-

Harha

-

Asiwan-Rasulabad

-

Jhalotar-Ajgain

-

Gorinda Parsandan

-

Purwa

-

Asoha

-

Mauranwan

7. Colonial Reconfiguration: The Expansion of 1869

The district was small. It did not yet include the famous Ghatampur or the Bihar pargana. The major restructuring occurred in 1869.

The Rae Bareli Transfer

The British, always seeking administrative efficiency, looked at the Baiswara tract. It was difficult for the Rae Bareli collector to manage the far-flung villages near the Ganga. Therefore, 6 Parganas were transferred from Rae Bareli to Unnao:

-

Panhan

-

Patan

-

Bihar

-

Bhagwantnagar

-

Magaryar

-

Ghatampur

-

Daundia Khera

The Lucknow Transfer

Simultaneously, Pargana Auras-Mohan was detached from District Lucknow and handed over to Unnao. It was initially placed in the old Tehsil Nawabganj.

The Wandering Tehsil:

The headquarters of this new tehsil had a nomadic existence. It was first moved to Mohan, and then finally, in 1891, it was permanently established at Hasanganj, where it remains today.

The same year (1869), the Municipality of Unnao Town was constituted, formalizing urban local governance.

8. Archaeological Gems: Sanchankot and Sujankot

While Navadevakula receives the scholarly attention, the district administration highlights Sanchankot as perhaps the most important ancient site.

Located in Village Ramkot, Pargana Bangarmau, Tehsil Safipur (55 km NW of Unnao city), Sanchankot is also known as Sujankot.

Who was Sujan Singh?

Local tradition attributes this fort to Raja Sujan Singh. These mounds often hide the secrets of the Rajput clans who controlled the region before the advent of the Delhi Sultanate. The presence of massive brick structures and high mounds suggests this was a fortified military outpost, likely guarding the approaches to Kannauj.

Unlike the ‘cursed’ city of Aundha Khera, Sujankot remains a silent, un-excavated treasure waiting for the spade of an archaeologist to reveal its secrets.

9. Conclusion: The Legacy of the Land

The history of Unnao is not linear; it is layered. Walking through Unnao today, one walks over the remains of Harsha’s empire, the revenue grids of Akbar, the hunting grounds of the Nawabs, and the cantonments of the British Raj.

From the Buddhist chants at Navadevakula to the administrative orders of the Collectorate, Unnao represents the quintessential Indian ability to absorb change while retaining ancient roots. It is a district that was literally built by the flow of history—and the Ganga.