Spend some time staring at the famous painting “Washington Crossing the Delaware,” and you can’t miss the ice. It’s everywhere. Cold weather became part of Washington’s military strategy, says Alex Robb, an educator at Washington Crossing Historic Park outside Philadelphia. “It does a lot to impede the crossing and endanger the whole operation,” he said, “but it actually becomes our shield.”

GraphicaArtis/Getty Images

At the end of 1776, after a string of losses, Washington’s army was on the verge of collapse. But Robb says that on Christmas, with ice forming in the Delaware River, the enemy assumed it was too dangerous for the Americans to cross.

They were wrong … and the cold weather handed Washington the element of surprise. His victory at Trenton was a sign that the war could still be won.

Robb said, “Looking back, had the weather proven more mild, they most definitely would’ve encountered resistance outside Trenton.” Just a few degrees made the difference between winning and losing a battle.

CBS News

At that time, Americans were used to colder winters. We know that from Thomas Jefferson’s meticulous, handwritten weather records. But since then, winter has gotten warmer. “Ever since Washington was here, there has been a steady increase,” said Jen Brady, a data analyst at the science non-profit Climate Central. Their research shows that average winter temperatures in the Philadelphia area have gone up and down over the years. But overall, they are now 5.5 degrees warmer than they were in 1970.

As for the current weather conditions around Washington Crossing, Pa., Brady said, “It will continue to snow. There will continue to be cold in cold places. But there will be less of it.”

“It’s a time machine”

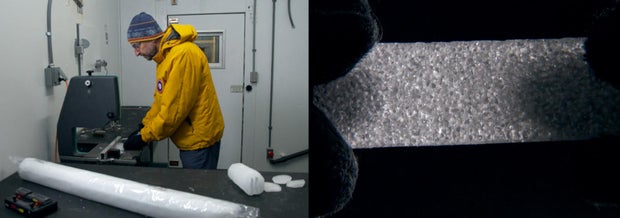

The best evidence of our changing climate comes from ice cores – long tubes of ice extracted out of glaciers in Greenland and Antarctica. And inside the ice core are perfectly-preserved air bubbles. The deeper you drill, the older the bubbles. “It’s this sort of magical way of going back in time,” said Eric Steig, a glaciologist at the University of Washington in Seattle. “It’s a time machine.”

CBS News

Steig showed us one ice core that dates from 1776, containing tiny pockets of air from that time. “So, like, you’re breathing a little bit of the air that George Washington breathed,” Steig said.

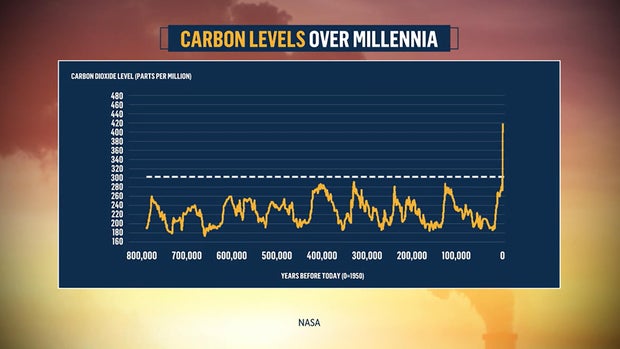

Those bubbles contain carbon dioxide, a gas that helps regulate Earth’s temperature. And for 800,000 years the carbon levels found in ice cores have gone up and down, but never above 300 parts per million – not until around 1800, when they started to take off.

What changed at that point to make that spike? “We began burning fossil fuels, and we’re doing it really fast,” Steig said.

CBS News

Since the Industrial Revolution, which began around the time of the American Revolution, our cars, factories, and power plants have been burning oil and gas and emitting massive amounts of carbon dioxide. That has led to warmer temperatures, which can intensify extreme floods, droughts and fires.

Steig said, “It would seem to me it’s good for people to understand things have changed, and will continue to change, and have an understanding of what to expect going forward.”

So, it turns out, around the time Washington looked out on the icy Delaware, there were two important pictures coming into focus: One, the story of America; the other, the beginnings of climate change.

And both continue to shape our world.

What would Washington say if he showed up in 2026? Steig replied, “You pluck somebody from that time period, they would see things having changed quite dramatically.”

For more info:

- Alex Robb, Washington Crossing Historic Park, Washington Crossing, Pa.

- Jennifer Brady, senior data analyst and research manager, Climate Central

- Eric Steig, glaciologist, College of the Environment, University of Washington, Seattle

- Thanks to Martin Froger Silva, University of Minnesota Climate Adaptation Partnership, and the U.S. Ice Drilling Program

Story produced by Robert Marston. Editor: Chad Cardin.

See more: