NOIDA: Guddi has quit two cooking jobs so she can be home at Sarfabad early each afternoon. Her six-year-old son walks back from school, and the fear of what might happen on the way has become overwhelming.“Once children leave the school gate, the school authorities say that they are not responsible,” she said. “That scared many of us. We can’t take chances.”Guddi’s decision was driven by panic as rumours of girls going missing swirled through village pockets across Noida, with unverified claims of child lifters spreading rapidly in recent weeks. Neighbourhood conversations and social media forwards have triggered panic among parents despite repeated assurances from police and NGOs that there is no evidence to support them.

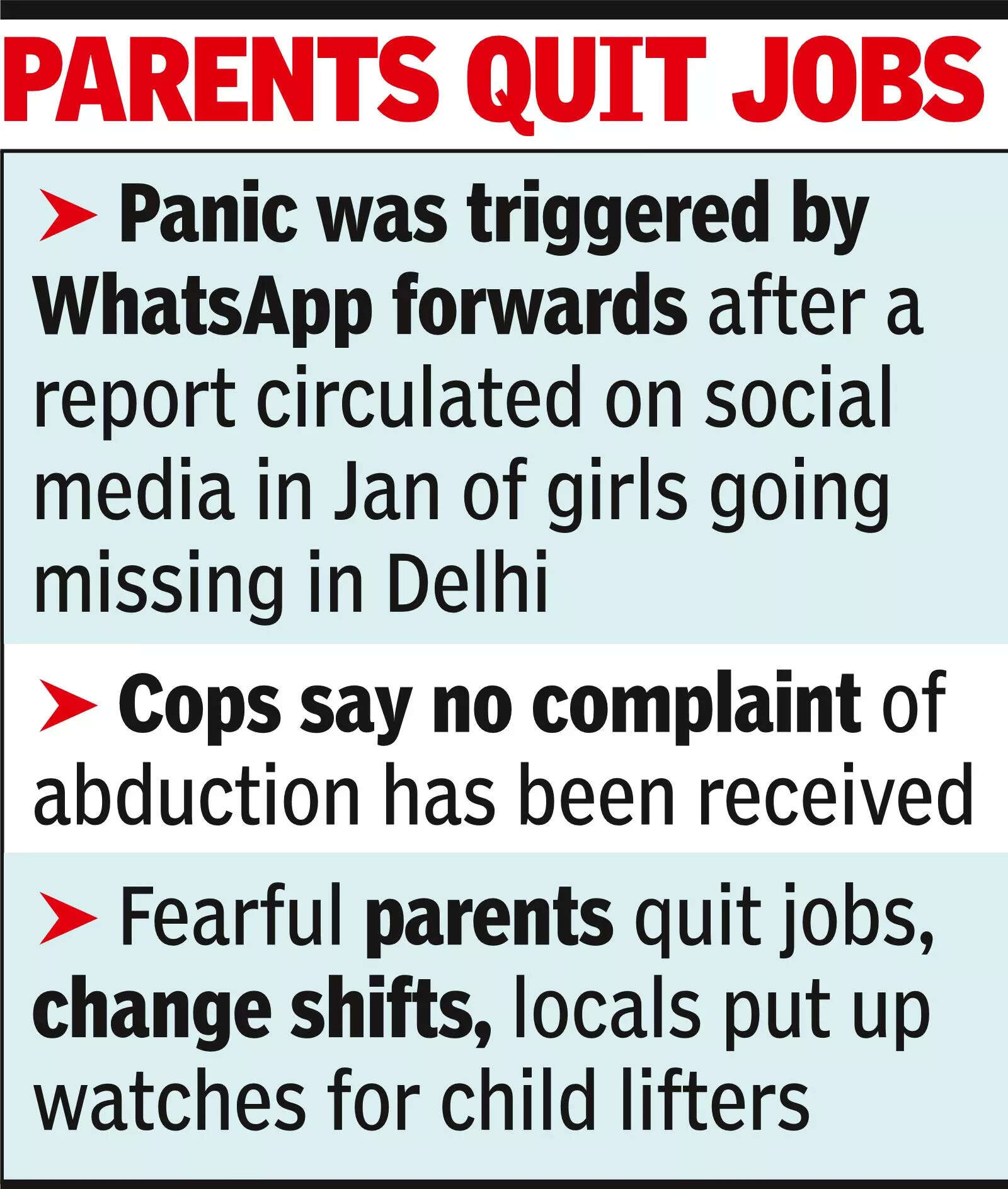

The latest rumours, similar to the pre-Covid hysteria about children going missing — which led to several lynchings and WhatsApp enforcing curbs on forwards — have been triggered by a report circulating on social media in Jan about girls going missing in Delhi, police said.Senior police officers told TOI that no complaint or verified report of a child abduction had been received. “These appear to be hoaxes, possibly triggered by misleading social media messages,” an officer said, urging residents to avoid spreading unverified information.Fear has nonetheless reshaped daily routines. Several women have quit jobs, men have changed shifts, children are not being sent to school, and locals are putting up watches for child lifters. “We rush back every day to be with our children,” said another domestic staffer from Sarfabad, who works in a nearby high-rise society. “Even if this turns out to be false, the fear is real.”Several non-profits and schools reported a visible impact. Mala Bhandari, founder of a Noida-based NGO, said attendance dropped sharply in centres operating in Nagla, Tugalpur and Haldoni. “Parents stopped sending children altogether,” she said. “When our team did field visits, we found no incidents.”Another NGO temporarily shut operations after first hearing the rumour from children. “We closed for a few days because attendance dropped,” the owner said. “When we cross-checked with families, no one had seen or knew a victim. It was unverified talk, but the panic had already spread.”Primary schools in nearby villages reported similar disruptions. A teacher in Harola said attendance dropped as rumours intensified, though follow-ups revealed no abduction cases. “Some absences were also for personal reasons, like family weddings,” she said.In some schools, the response was precautionary. Sunita, a teacher at a private school in one of the villages, said the management circulated consent forms asking parents to pre-declare how children would commute and who would collect them. “Students are released only to authorised guardians,” she said. “There are no such cases here that we know of, but awareness feels necessary.”A police officer said such episodes are not new. Similar rumours have surfaced in the past, briefly fuelling fear before being debunked. The concern, they added, is that misinformation, especially when amplified online, can quickly disrupt community life and strain trust.The panic echoes 2018 and 2019, when India witnessed a spate of mob violence sparked by suspicions of child lifting, many of them triggered by viral WhatsApp messages. According to data compiled by Centre for Study of Society and Secularism, there were 41 reported incidents of mob violence in 2018 linked to such rumours, making child-lifting fears the leading trigger that year. Though National Crime Records Bureau does not maintain data for mob lynching, making comprehensive tracking difficult, at least 20 people were killed in the mob attack during the period.